Fabrica is a communication research centre based in a campus in Treviso centred on a 17th-century villa, restored and significantly augmented by renowned Japanese architect Tadao Ando.

Established in 1994 from a vision of Luciano Benetton, Fabrica offers young people from around the world a one-year scholarship, accommodation and a round-trip ticket to Italy, enabling a highly diverse group of researchers. The range of disciplines is equally diverse, including design, visual communication, photography, interaction, video and music.

Fabrica aims to inspire a specific creative category of young “social catalysts” who, at the end of their experience at the centre, will continue their work independently.

Today more than ever, Fabrica’s research is a cross-disciplinary commitment wherein communication interacts with other vital sectors like the economy and social and environmental sciences and, through incessant experimentation, is unfailingly alert to the changes and trends of modern society.

As Luciano Benetton said “fabrics is a place, for reciprocal learning, in the truest sense of the phrase”.

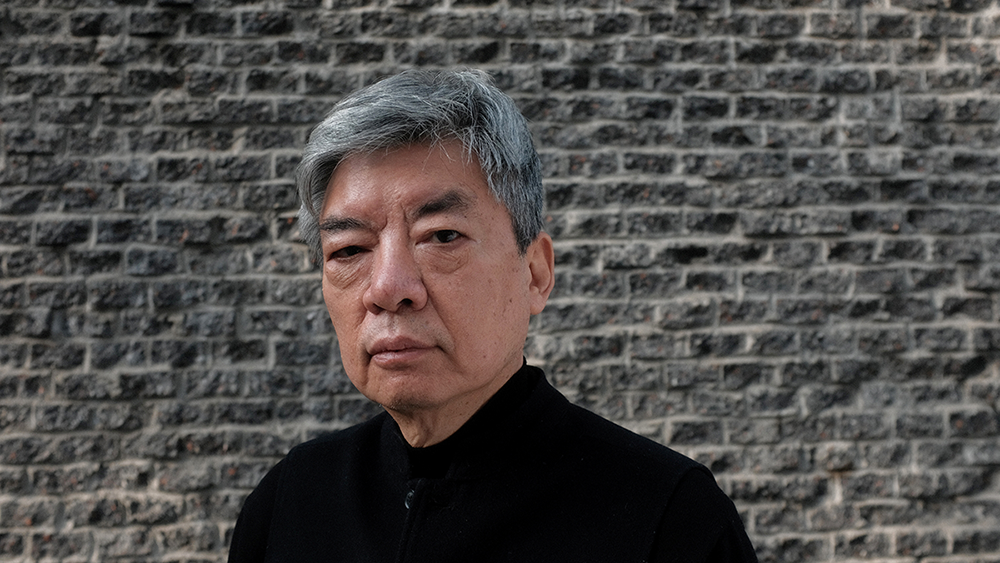

To those who were born and raised in North East of Italy, where beautiful villas and ancient palazzi are part of the landscape, it seems only natural to conserve this legacy for future generations. Therefore valuing and respecting this environment was the task given to the Japanese architect Tadao Ando from Luciano Benetton.

So the plan for Fabrica came to Tadao Ando spontaneously. There was, in fact, a seventeenth-century villa and several outbuildings already on the site. To allow the scenery and the memory of the environment to continue to flourish, and to restore the existing building and give it new life, the Japanese architect planned most of the new installation underground so as to highlight the beauty of the landscape. However, uniting the architecture of the past and that of the present does not simply mean representing the two extremes. He restored the ancient architecture respecting its character, so that the history it embodies will stay alive; at the same time the new area can respond to this history in its own, equally unique, way.

Visiting Fabrica you can find architecture of the past and the present; the two put their trust in, and draw inspiration from, each other. The role of the new architecture is to bring out the charm and strength of the ancient villa and to give birth to a reciprocal, cathartic relationship between old and new in an atmosphere of complete harmony, transcending the limits of a specific period. Therefore, even the transit areas, which normally play a secondary or insignificant role, have been given due attention. They act as places for communion and communication between people, between people and history or nature; places which encourage dialogue between people from different backgrounds. They take the shape of squares atriums, and galleries, distributed throughout the area. Elements, such as natural light and wind, have been invited to become part of the architecture so they may mitigate contrasts.

I have always believed that the very nature of architecture gives it an important social function and that it is the fruit of a collective commitment. Apart from a few rare examples, architecture cannot be created without a true process of collaboration. The architect is immersed in the historical and social context that surrounds him and he interprets his awareness in his work. In less abstract terms, the building, starting from the construction site, grows and takes shape through the contribution of all those – workmen and engineers – who work on it.

People involved in building should have a vision of the overall plan, not just of their individual job, if the best results are to be achieved. When I saw the people working on the Fabrica construction site I was highly stimulated; their passion for “building”, in the broadest sense of the word, particularly impressed me. When I talked to them I realised that they had understood my, and the client’s, vision and that they could visualise both the overall project and the role of each individual. They are proud of what they build, therefore they put passion into their work. (Tadao Ando)

You can see that the skill of architects of the past, such as Carlo Scarpa, lives on in the quality of the work of the craftsmen who did the Venetian stucco, and also in the work of the engineers whose set cement is just as good as the best Japanese cement-work. This is demonstrated by the walls that have preserved their original quality.

In the realisation of the new buildings, the great Japanese architect made extensive use of exposed reinforced concrete, the stylistic signature of his work. Ando created the laboratories, of ces and a helicoidal library around an elliptical, porticoed square positioned approximately ten metres below the natural ground level which is accessed by a broad staircase.

The original part of the villa, the “barchessa” buildings (long porticoed wings typical of Veneto villas) which now house laboratories and an auditorium, was renovated with philological attention both in the choice of materials as well as construction techniques: antique brickwork and marble nishings, Palladian-style and wooden ooring.

A series of 12-metre high columns in monolithic architectural concrete crosses the space and is re ected in the water: a veritable architectural quest which unites the dictates of Ando’s work to those of the traditional culture of the Veneto villa.