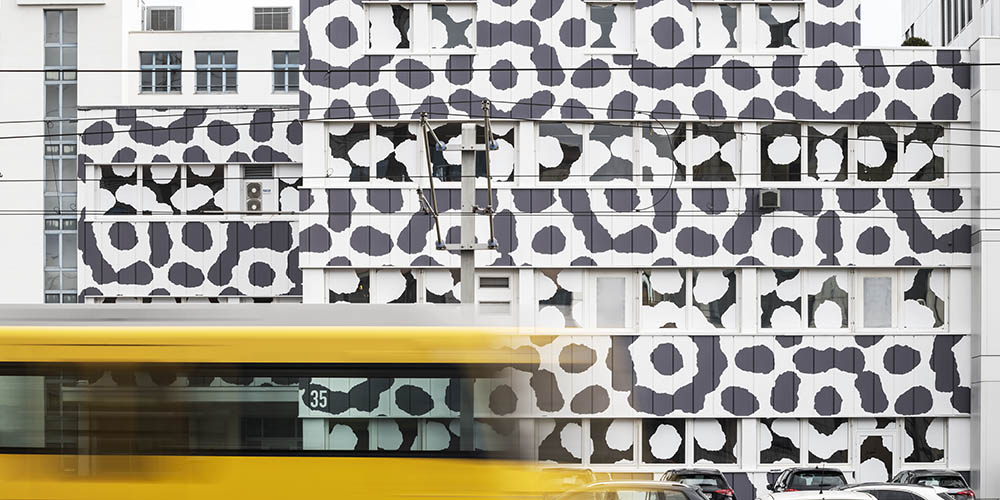

Called SW35, the provocative four-story structure designed by the renowned German architecture firm J.MAYER.H is the physical home for a group of startup companies working in the green tech sector.

Right now, as humanity realizes its current limbo may last much longer than originally expected, a buzzword has emerged: liminal.

In architecture, a liminal space is one of transition—a staircase, a hallway, or threshold (the literal meaning of the Latin root “limen,” from which liminal derives). Psychologically, the liminal is about rites of passage, which are by definition not easy, but these ultimately lead to growth and transformation—transitions always head somewhere, and they can mean possibility, hope, evolution, moving from old to new.

The notion of a loaded-yet-liminal space is just one of the starting points that J.MAYER.H considered in transforming the façade of a nondescript nineteen-seventies-era office building in Stuttgart from dingy white to bold graphic patterns, to reflect its current repurpose as an innovation lab.

Called SW35, the four-story structure (part of an ensemble that German technology entrepreneur Ulrich Dietz acquired alongside his purchase of automotive company Mercedes-Benz's “Lab1886” innovation hub in 2020) is now a physical home for a group of startup companies working in the green tech sector.

Now operating under the “umbrella” name 1886Ventures, When still owned by Mercedes-Benz, Lab1886 spawned Drive Now, moovel, and other car-sharing ventures, the companies in the building focus on research, and developing new business models around hydrogen technologies, future mobility, and circular economy platforms.

Dark gray-and-white marks splash across SW35's facade, creating an eye-catcher in a bleak industrial zone.

At first the repeating, organic-looking blobs appear to be a stylized leopard print, the kind popular on clothing for blurring contours and attracting attention, but not quite: they are instead riffs on one of the data-protection patterns that line envelopes, meant to shroud or camouflage sensitive information inside—PINS, confidential correspondence, and the like.

This time these marks appear not as tiny squiggles but rather as bold supergraphics, as large as a human being, on the building's exterior.

Painted on the facade where it's metal, appearing as sticky film where it's glass, J.MAYER.H's found graphics provide a visual pop.

The office's founder Jürgen Mayer H. has been collecting data-protection patterns for more than 25 years, incorporating variations on them not only onto architectural facades (ironically, a facade in architecture is known as a “building envelope”—a connection that in this case gains extra meaning), but also sculptures, art objects, carpets, even installations in museums like the Berlinische Galerie in Berlin, the MoMA in New York, the SFMOMA in San Francisco, and biennials in Venice, São Paolo, and Shenzhen. He sees their mashups of blurred letters, numbers, and shapes as a “primordial soup” of signifiers; rogue, unregulated, and individual.

By design (and paradoxically) they also blur lines and details and ultimately keep secrets, a quality that's increasingly difficult in an era in which so much of human life is heavily surveilled and tracked, and in which privacy and anticipation come at a high premium.

It's a bit like the “lesson” of “how to be invisible in plain sight” from artist Hito Steyerl's video work How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic mov.file from 2013. The piece traces how surveillance plays out in modern culture on the large scale (oversize resolution targets in the California desert) as well as the small (pixel-size): in a deadpan voice, a computer-generated narrator claims “most important things want to remain invisible.” SW35 cleverly and appealingly makes something invisible as it pulls the eye; what happens inside this place stays inside this place; that is, until it's ready for the big reveal.

An additional conceptual layer connects to both the region and to what the companies in the building are working on, and one that J.MAYER.H took most to heart in conceptualizing his intervention.

Southern Germany is home to the country's revered automotive industry, and prototype cars have been tested for decades on the highways and roads around Stuttgart before launching on the consumer market.

Like SW35, these cars are entirely cloaked in squiggly lines and curves, the vehicles' new features thus less visible to camera-wielding car fanatics keen to know what's next. These obscuring visuals are known as “dazzle camouflage,” a hearkening to the dazzle ships of the World Wars—then, tankers and submarines appeared in black-and-white stripes and diagonals to confuse enemies and make the vessels difficult to track.

The “development mule” cars even have a name—Erlkönig (“Erlking”). The name originates in a Johann Wolfgang von Goethe poem in which the Erlkönig is a sinister wood fairy, but its designation here comes from two German journalists who published a column in the magazine auto, motor, and sport in the 1950s after their photographs of unlaunched cars appeared in its pages.

The column began with the line “Who drives there so fast through rain and wind?” (a take on the Goethe poem's first line: “Who rides there so late through the night dark and drear?”). German automakers have added dazzle camouflage patterns to cars ever since: to confuse but also intrigue anyone photographing them, and to entice customers to always desire newer models in a now-common marketing strategy. The name Erlkönig has stuck.

Dazzle could be seen as an intentional visual glitch, and it's infiltrated fashion and art in recent years: “Normally with camouflage you blend an object into its background. But with dazzle, you blend an object into itself,” says German artist Tobias Rehberger, who in 2014 camouflaged a boat for the Liverpool Biennial and centenary of the outbreak of World War 1.

“The Erlkönig is different from dazzle ships,” says Jürgen Mayer H. “Dazzle warships want to make it difficult to be hit or shot. Patterns in the Erlkönig car want to attract attention and be seen, but don't want to divulge too much information. They want to tease, push, and pull your curiosity. And yet with both, it's a power game: both want to irritate whoever is shooting.

SW35 creates a more playful kind of power game. Ulrich Dietz commissioned J.MAYER.H to capture the essence of the activity here, connecting to mobility, innovation, and testing.

The building is also a prime example of reusing existing architecture and redefining programs using minimal means; a simple but high-impact transformation of not only a structure, but an entire district.

Like an urban QR code, the exterior patterns protect as they provoke; they shield the innovation inside from peering eyes and minds, but at the same time make it clear that something interesting is happening. (Dietz also collects conceptual art, some of which is on view inside SW35 as, he says, creative and conceptual inspiration for those working here.)

And so we return to notion of the liminal space; and the perpetual tension between inside and outside. Those outside can't (yet) know what's going on in these rooms behind the reverse-pattern shades; drawn when the sun shines and providing contrast. This layer between public and private, or exposed and discreet, is again always in negotiation. And as much as boundaries help us understand the structure of our societies, the construction of spaces depends on constantly questioning the operations of these definitions. They mutate, allow us to negotiate new forms of belonging. Behind this cloaked exterior is a threshold; a zone of transition in which impulses become ideas, which in turn become novel ways of doing things in our world.

SW35 | Project Data

Realization: 2021

Client: RB-Real Estate GmbH / Ulrich Dietz

Partners in Charge: Jürgen Mayer H., Hans Schneider

Team: Noah Ehlers, Paul Rindt

Architect on Site: Heike Schaefer, Architect, Stuttgart

Lighting: Lichttransfer / Katrin Soencksen, Berlin

Fotograf: David Franck